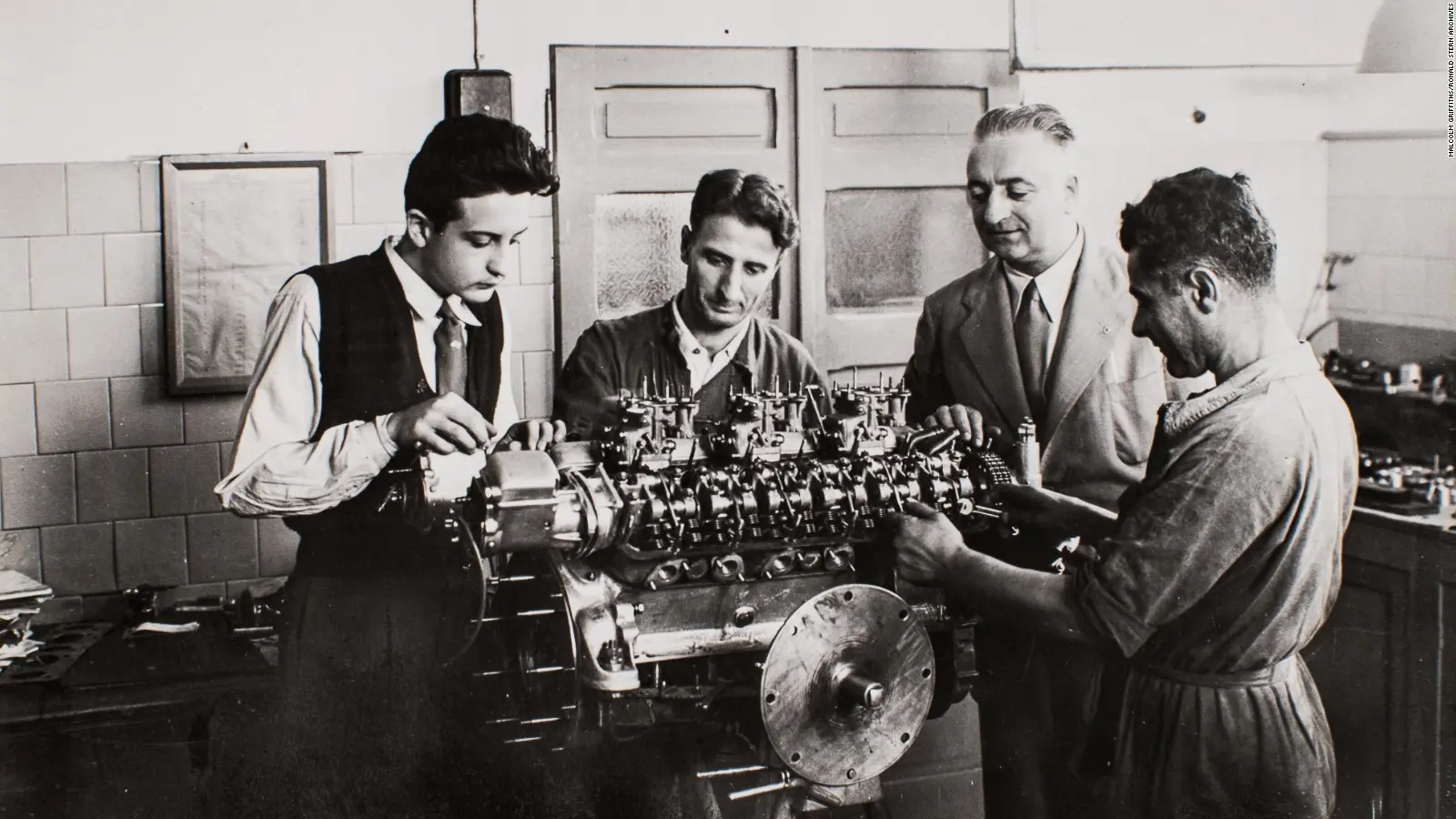

Alfredo “Dino” Ferrari (left) alongside his father Enzo at the heart of the factory - long before the son's name would define an entire line of cars.

The Role of the Dino Brand

The Dino name had been introduced earlier as a way to honor Alfredo “Dino” Ferrari and to differentiate smaller-engined cars

from Ferrari’s twelve-cylinder flagships.

By using the Dino badge for the 308, Ferrari was able to draw a line between tradition and what came next.

Under this strategy, V6 and later V8 models could explore new layouts, production methods, and market segments without directly challenging the brand’s established image.

For many enthusiasts, the name Dino was inseparable from the earlier 206 and 246 models — compact, elegant cars closely associated with Ferrari’s racing spirit.

They defined the emotional image of the Dino brand long before the 308 GT4 appeared.

The GT4, being larger, more angular and more practical, stood in contrast to this image — and therefore faced a hard time, getting compared with cars it was never meant to replace.

Understanding this contrast is essential, as much of the GT4’s early criticism was rooted not in its own shortcomings, but in the expectations inherited from its predecessors.